The Nails that Attest the Presence of Roman Legionary on the Temple Mount

In these days of “Between the Straits,” (the days between the 17th of Tamuz and the Ninth of Av), we remember the battles that led to the destruction of the First and Second Temples and ended the last independent Jewish state in the Land of Israel, until the establishment of the modern State of Israel.

Although the Jews were ultimately defeated in the Great Revolt against the Romans (66-70 CE), they had some small victories along the way. One of those victories came about on the 5th of Tammuz, about a month before the destruction of the Second Temple. The fighting was already well underway; the Romans had breached the walls of Jerusalem, captured the Antonia Fortress, and were on the verge of breaking into the Temple Mount. But the Jewish fighters managed to push them back.

According to Josephus’ description (The Jewish War VI, 81–92), it seemed that the Jewish rebels were about to win on that day (the 5th of Tammuz), until a centurion named Julian pushed back the Jewish defenders, broke into the Temple Mount, and almost turned the tide of victory toward the Romans. However, one item of his clothing betrayed him, as he stumbled and slipped when he tried to run in his hobnailed sandal-boots on the smooth stone floor.

Let’s go back a few decades. King Herod initiated a massive construction project to expand the Temple and the Temple Mount compound. He imported colorful stones of various types for paving the courts with beautiful opus sectile (“cut work”) floors. These floors, made of precisely cut colored polished stones, remained smooth over the years since wearing shoes was forbidden on the Temple Mount, and this rule might have applied to the extended plaza as well.

The Talmudic legendary literature has it that there was one exception to this rule: Alexander the Great, who was told during his visit to the Temple, “My lord the king, remove your shoes and wear these slippers because the floor is slippery” (Scholion to Megillat Ta‛anit, Sivan; Bereshit Rabbah, 61, 7).

But Centurion Julian did not wear slippers designed to prevent slipping on stone floors. Instead, he wore military sandal-boots called caligae. As Josephus describes: “for as he had shoes all full of thick and sharp nails as had every one of the other soldiers, so when he ran on the pavement of the temple, he slipped, and fell down upon his back with a very great noise, which was made by his armor.” (The Jewish War 6.1: 85).

His hobnailed shoes were evidently designed for the softer earth of the battlefield, not for running on polished floors. Julian’s fall halted the Romans’ advance that day, and they only managed to break into the Temple Mount a few weeks later.

The hobnailed sandal-boots were a distinctive mark of Roman soldiers, and the legends of the destruction are filled with stories about the dangers associated with hearing the sound of approaching hobnailed sandals – the military sandal-boots of the Roman soldiers, discovering footprints indicating their presence in the vicinity, and even instances in which the boots themselves caused death (Jerusalem Talmud, Shabbat VI, 2; Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 60, 2).

This is also how the word calgas entered the Hebrew language, referring to a ruthless enemy soldier. Even the name of Emperor Caligula (31-41 CE) derives from these sandal-boots, meaning “little sandal-boot.” This nickname stuck with him because, as a child, he used to dress up in a soldier’s uniform and wear miniature caligae sandal-boots.

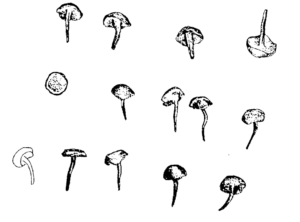

The caligae nails were short, mushroom-shaped, some with flat heads and others semi-spherical. In cases where the full length of the nail survived, it is evident that its point was bent to prevent potential injury to the foot. The nails secured the sole, which consisted of three layers. Each boot had between 40 to 150 nails. Sometimes the nails were only around the edge of the sole, and sometimes the sole was completely filled with nails. The nails prevented the leather sandal-boot soles from wearing out prematurely due to contact with the ground.

The memory of the horror of the caligae remains, and almost 300 years later, it was preserved with the Pilgrim of Bordeaux, who recounted that one could still see in his days paving stones on the Temple Mount with centuries-old bloodstains, along with marks made by hobnailed sandal-boots.

While, in the Sifting Project, we have not found stones as described in this account, we do find many stones from the Temple Mount’s paving, some with scratches or grooves possibly from ancient times, as well as over a hundred shoe nails typologically dated to the Roman period. Some are likely from caligae sandal-boots, while others may be from civilian hobnailed shoes.

Don’t want to miss any updates from the Sifting Project? Follow us on our Telegram channel: https://t.me/tmspupd

Discover more from The Temple Mount Sifting Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Very interesting story. Thank you for posting.

BR

Jan