Stone of the Siege: 10th of Tevet and the Defense of the Temple Mount

On this 10th of Tevet, a day marking the onset of the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem, we reflect on the transition of the Temple Mount from a sacred center to a besieged stronghold. A recent discovery from the Temple Mount Sifting Project, a small, meticulously rounded stone recovered by one of our frequent visitors, 12 year old Noam Spivak, provides a tangible entry point into the mechanics of antiquity warfare.

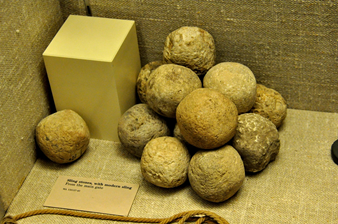

Measuring 3 cm in diameter and weighing 20.38 grams, the artifact is a bit smaller than the “standard” 4–7 cm spherical flint and limestone projectiles frequently recovered from major destruction layers like those at Lachish. However, its morphology suggests it may have functioned as specialized sling ammunition. In ballistics, such lighter stones prioritize launch velocity and range over the sheer crushing force of heavier siege stones. In the hands of a trained slinger, a 20g projectile could achieve a release velocity exceeding 160 km/h (100 mph). While larger projectiles were capable of generating approximately 38 Joules of kinetic energy, sufficient for lethal blunt-force trauma, these lighter stones were likely utilized for high-velocity precision fire.

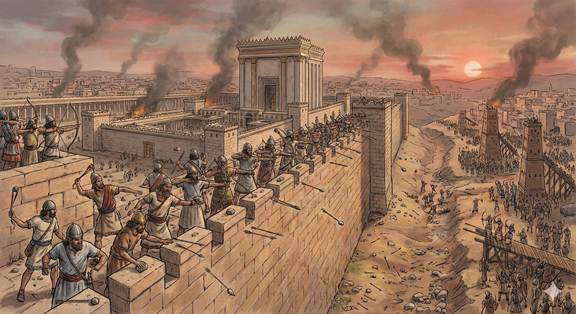

This slingstone joins a handful of other flint and limestone spherical stones found in the Sifting Project, usually larger in diameter than this one. The presence of such a projectile on the Temple Mount underscores the tactical nature of the Babylonian siege (or perhaps the Assyrian siege 115 years earlier). The sling was equally vital for the aggressor. As Babylonian forces advanced on the 10th of Tevet, their slingers would have used high-velocity stones like this to provide suppressive fire, clearing the Judean defenders from the parapets and gate towers so that siege ramps could be constructed.

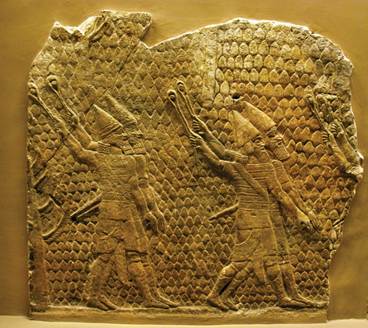

The sling is often colloquially relegated to the status of a “shepherd’s weapon,” yet the archaeological and textual records reveal a highly organized military application. The biblical account in Judges 20:16 describes an elite unit of 700 Benjamite slingers capable of slinging a stone at a large distance without missing, while 2 Chronicles 26:14 notes that King Uzziah’s state logistics specifically included the preparation of “stones for slinging” for the national armory.

Archaeologically, these projectiles are frequently misclassified in domestic contexts as hammerstones or weights. It is only through contextual analysis—identifying concentrations in defensive sectors or battle debris—that their martial function and date become clear. Due to this difficulty, and the mixed context of the finds sifted from the Temple Mount’s soil, we can only raise the possibility of this being a slingstone used in a siege of Jerusalem.

Whether launched by a Judean defender or a Assyrian, Babylonian or Roman attacker, Noam Spivak’s find bridges the gap between historical narratives and the material reality of the conflict that defined Jerusalem’s history. And on this special day, it may stand as a silent witness to the moment 2,600 years ago when the peaceful courtyards of the Temple Mount were first breached by the sounds and stones of war.

Measuring 3 cm in diameter and weighing 20.38 grams, the artifact is notably smaller than the “standard” 4–7 cm spherical flint and limestone projectiles frequently recovered from major destruction layers like those at Lachish. However, its morphology suggests it may have functioned as specialized sling ammunition. In ballistics, such lighter stones prioritize launch velocity and range over the sheer crushing force of heavier siege stones. In the hands of a trained slinger, a 20g projectile could achieve a release velocity exceeding 160 km/h (100 mph). While larger projectiles were capable of generating approximately 38 Joules of kinetic energy, sufficient for lethal blunt-force trauma, these lighter stones were likely utilized for high-velocity precision fire.

This slingstone joins a handful of other flint and limestone spherical stones, usually larger in diameter than this one. The presence of such a projectile on the Temple Mount underscores the tactical nature of the Babylonian siege (or perhaps the Assyrian siege 115 years earlier). The sling was equally vital for the aggressor. As Babylonian forces advanced on the 10th of Tevet, their slingers would have used high-velocity stones like this to provide suppressive fire, clearing the Judean defenders from the parapets and gate towers so that siege ramps could be constructed.

The sling is often colloquially relegated to the status of a “shepherd’s weapon,” yet the archaeological and textual records reveal a highly organized military application. The biblical account in Judges 20:16 describes an elite unit of 700 Benjamite slingers capable of slinging a stone at a large distance without missing, while 2 Chronicles 26:14 notes that King Uzziah’s state logistics specifically included the preparation of “stones for slinging” for the national armory.

Archaeologically, these projectiles are frequently misclassified in domestic contexts as hammerstones or weights. It is only through contextual analysis, identifying concentrations in defensive sectors or battle debris, that their martial function and date become clear. Due to this difficulty, and the mixed context of the finds sifted from the Temple Mount’s soil, we can only raise the possibility of this being a slingstone used in a siege of Jerusalem.

Whether launched by a Judean defender or a Assyrian, Babylonian or Roman attacker, Noam Spivak’s find bridges the gap between historical narratives and the material reality of the conflict that defined Jerusalem’s history. And on this special day, it may stand as a silent witness to the moment 2,600 years ago when the peaceful courtyards of the Temple Mount were first breached by the sounds and stones of war.

Discover more from The Temple Mount Sifting Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

On terminology: The stones are slingstones, launched from stone-slings (the rope and pouch sets).

Hi Ronald. Noted. Thank you