Thanksgiving — Then and Now

Long before turkey and pumpkin pie, the holiday of Shavuot was the ancient Israelite prosperity “Thanksgiving,” celebrating the end of the grain harvest season and the bringing of the bikkurim, the first produce, to the Temple in Jerusalem. Pilgrims arrived with baskets of their fresh goods, singing and rejoicing as they joined a festive procession that transformed gratitude for the land’s bounty into a joyful public celebration.

As Thanksgiving approaches, we’re reminded that the idea of giving personal thanks to God for the blessings, bounty, and miracles in our lives is deeply rooted in the biblical tradition. Leviticus 7:11–15 introduces the concept of the Korban Todah, the Thanksgiving Offering. This passage gives the basic framework: it is a type of peace offering accompanied by loaves of bread that must be eaten within a limited time.

The Talmud (Berakhot 54b) goes further, explaining who is obligated to show thanks: someone who has survived a dangerous journey by sea or desert, recovered from serious illness, or been released from captivity. These details transform the offering from a general act of gratitude into a response to specific life-saving events.

The Korban Todah was unique: it included one animal and forty loaves of bread—thirty unleavened and ten leavened—which the Torah forbids leaving uneaten beyond its permitted time—one day and one night. Why so much food in so little time? This leaves the person bringing the offering with no choice but to invite others to join the meal. Gratitude became a shared experience, turning a private moment into a communal celebration. It wasn’t just a personal sacrifice to God; it was a full-on party with friends.

After the destruction of the Temple, this practice evolved into new forms: Birkat HaGomel, a blessing recited publicly in synagogue; the recitation of Psalm 107, praising God for deliverance; and the custom of holding a Seudat Hoda’ah, a thanksgiving meal with family and friends.

Communal meals in ancient times were usually eaten while seated on the ground, reclining or sitting cross-legged, often on mats or woven carpets. This is still practiced today among traditional Bedouin families, who sit in a circle, share a common dish, dip their bread, and eat with their right hands from the portion nearest to them, much as described in the book of Ruth (2:14) and Proverbs (19:24). This is not a coincidence: Bedouin hospitality preserves patterns deeply rooted in the same desert cultures that shaped ancient Israel.

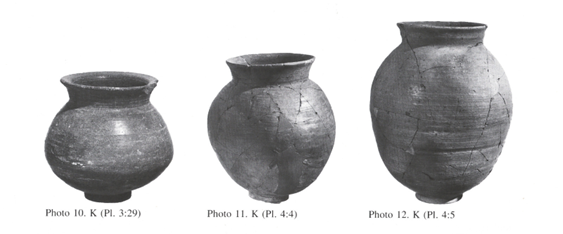

The Temple Mount Sifting Project has uncovered fragments of First Temple-period kraters—oversized mixing and serving vessels—used for communal feasting. Several krater types that are very common in the southern and coastal region of Israel and even in northern Israel were found in abundance in the Temple Mount Sifting Project’s krater assemblage, while they are rare or non-existent in soil samples taken from other locations in Jerusalem (with the exception of an Iron Age refuse pit from the eastern slopes of the Temple Mount that was also sifted by us, and the pottery found in the Ophel excavations south of the Temple Mount). The data may point to pilgrims bringing their traditions to Jerusalem during pilgrimage seasons and thanksgiving feasts.

From the late Second Temple period, we’ve recovered thousands of cooking-pot fragments, many possibly deliberately broken and removed to refuse concentrations after being used for sacrificial meals. In this period, it was easier and more frugal for pilgrims to simply buy their wares locally, as the massive pottery industry at Binyanei Ha’uma would suggest. Evidence of the food supply for the pilgrims has been found in the abundant remains of animal bones in the city’s refuse dumps near the Temple Mount, as well as on the Temple Mount itself. These bones and vessels are the physical remains of our ancestors’ pilgrimages and gratitude feasts.

Today, as we sift through the soil of the Temple Mount and uncover fragments of that sacred past, we see how timeless this message is. Whether through offerings in Jerusalem or sharing a turkey on Thanksgiving, the lesson endures: gratitude is meant to be yummy and shared.

Discover more from The Temple Mount Sifting Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!