Not as you thought: The most significant archaeological work is in the lab and not at the dig…

Many people ask us, what kind of processing do we do on our material before publishing – and why does it take so long? For a quick answer, take a look at the photo below – it tells us a little about the donkeywork behind the processing of artifacts. If you’d like to hear more about the behind-the-scenes work in our project, read on.

Thousands of bowl rims from the Byzantine period, of the Fine Byzantine Ware type – Form 1, Variant B/D

As opposed to salvage excavations, in an academic excavation the main core of the archaeological work is carried out in the lab and not in the field. The average yearly excavation work consists of around a month of excavation on site; the remainder of the year is taken up with studying and processing the finds in the lab. In the case of the finds from the Temple Mount Sifting Project, the challenge of processing the material is more difficult since the artifacts were not uncovered in-situ, and hence we need to apply complex statistical calculations in our research with the aim of reconstructing the original context of the more frequent finds.

The collections of artifacts from the Temple Mount sifting process arrive at the lab as a kind of enormous jigsaw puzzle with hundreds of thousands of pieces. Initial sorting is carried out at the sifting site, where the finds are sorted by material (earthenware, metal, animal bones, etc.) and by major categories of find (pottery vessels’ rims, oil lamps, marble floor tiles, opus sectile floor tiles, sawn bones, burnt bones, etc). In the laboratory, the material undergoes further sorting, first by dating into time periods and then into classes of artifact (e.g. bowls, jars, cooking vessels, jugs, juglets etc.). In the next stage, the resolution of the sorting increases: each class is sorted into types (using criteria of shape, material, style, decoration etc.). This stage constitutes the majority of the sorting work, and is termed “typology”. The next stage, as seen in the above photograph, entails sorting artifacts of each type by the area in which they were found in the soil dumps removed from the Temple Mount.

In a regular archaeological excavation that is carried out on site, archaeologists study and publish the finds in respect to the areas in which they were found, and the study of certain areas, and sometime even categories of artifacts, may be postponed to a later stage. In our case we cannot do this since the study of all the artifacts is inter-related – as in our analogy of the jigsaw puzzle. All the artifacts must be sorted first in order to understand the rest of the artifacts. This is because different types of artifact from the various time periods represented are scattered over the different parts of the dump. However, they are not scattered uniformly like a well-mixed salad, but are distributed over the different parts of the dump in varying patterns of concentration. What’s interesting here is that types of artifact that apparently came from the same original context are scattered in similar patterns – that is to say, they have similar statistical distributions over the areas of the dump. For this reason, where the dating or identity of some types of artifact is unknown, this information can be deduced from a different type of artifact displaying a sufficiently similar distribution in the dumps (whereas in a conventional excavation, this information may be deduced from other, identifiable, artifacts found in the immediate vicinity). The project has developed a novel statistical method which helps deduce the original context of artifacts extracted from dumps and earth fills.

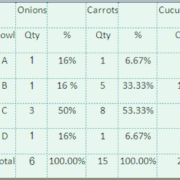

For the statistical analysis of the pottery, we chose to sample only shards from rims of vessels. A vessel’s rim is its most indicative part in identifying the vessel type. In a regular dig, archaeologists generally discard most shards, retaining only those which were part of the vessel’s rim, although whole vessels may also be found, but usually they are significantly fewer than the pot shards. In our case, our pottery finds consist only of broken parts of vessels, shards. We have reached the stage where we have finally finished the typological sorting of the majority of the pottery shards, and have started to count and record them in a database as a precursor to the initial statistical analysis. To this end, we have enrolled volunteers (and here we acknowledge the great help given by Sari Sapir, Michael Swirsky and Dr. Ron Beals!). Since we’re talking here about a fantastic opportunity to learn about Jerusalem’s pottery history through the ages and get some great hands-on experience on the subject, we offered the task to archaeology students, at which point Keren Schwartzman, a 2nd year archaeology and chemistry student at the Hebrew University, jumped at the chance. This work includes sorting shards of each type by the dump section in which they were found, and then counting the groups and entering the data into the database. To this data are added measurements taken from samples of pot shards from each type, such as: maximum diameter, average circumference conservation percentage and more.

Exciting, no? Ok, so we got a little carried away… but ladies and gentlemen, this is archaeology! It’s fun to dig, but to reach significant conclusions we need to invest in exacting and thorough research. We’re dealing here with little kettle knobs, because each kettle has its own definitive kind of knob. When we start to understand the significance of each kind of knob, the slant of a rim, the thickness of a vessel wall, the hardness of the earthenware material, decorations and other properties, then business starts to get really interesting, and we can start to throw new light on the history of Jerusalem.

Haggai Cohen, Researchers Manager, in deep study of the shard he holds…

Discover more from The Temple Mount Sifting Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Congratulation! What a most real picture of truth against the lies from the Islamic side¨¨

We also have to think about the massacre of 1929 caused by the infamous Mufti Amin Al-Husseini using the temple mount as motiv.

Bring the movie to the media!

God bless Israel!

Hanspeter .