A Piercing Insight Into Ancient Beads

When coming into the sifting site, groups are shown into a gallery where a few of our finds are displayed, and our guides are presented with a tough choice – with limited time, which do you point out and discuss?

Personally, I try to never skip this necklace, which sums wonderfully exactly what we do here.

At first glance, one may think this is simply an artifact discovered in the sifting, which may tell a single story from a single period, but one important part of this item isn’t a recovered artifact – the string. What we have in front of us are in fact 35 different beads, discovered separately, each telling the story of a different necklace or other pieces of jewelry and articles of clothing.

But at this point we were a little stomped – how can we tell? Some fields of archaeology, such as pottery, glass vessels, coins, or weights, have been intensively studied for many years, and experts abound who are able to securely identify and date these artifacts. Other types of artifacts, such as nails, dice, or combs, still don’t have their own experts, and can be quite difficult to tell if an object is decades, centuries, or millennia old.

So, we focus on more manageable research, and these finds sit on the sidelines, until a better methodology crops up. Such is the tale of our stone beads.

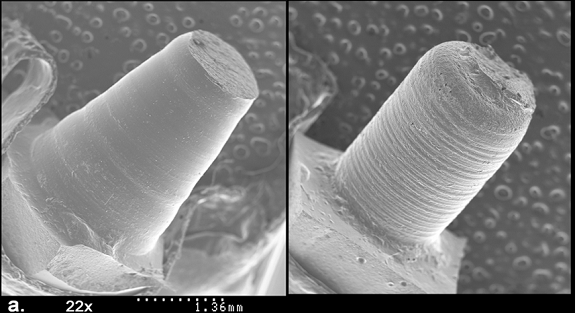

A few years ago, a member of our research team attended an archaeological conference and met Dr. Geoffery Ludvik, a young scholar from the University of Wisconsin-Madison who, as a student of Dr. Jonathan Kenoyer, was the first bring to Israel the technique of studying stone beads not just by their shape and material, but also by examining the technique used to drill them. Apparently, successfully drilling through a bead requires quite a skilled laborer. This is evidenced in ancient sources as well, and the Talmud (B. Metz. 12b; Ketub. 40a) notes that “pearl piercing” as a high-value occupation. As with many specialized crafts, we can sometimes discern the workshop traditions which they followed.

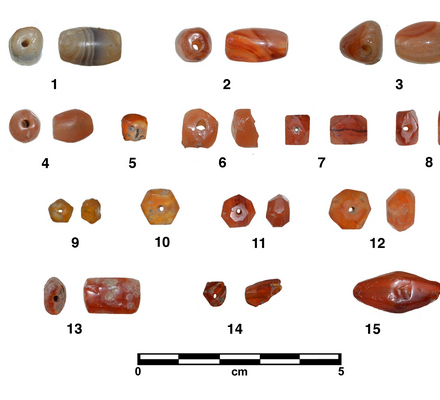

Dr. Ludvik agreed to study some of our beads – specifically, beads made from carnelian and agate – two minerals that have been popular with bead makers for thousands of years. The beads were examined in the lab, and some of the beads had casts made of them, to be further examined under a microscope’s lens.

Unsurprisingly, the results were mixed. As expected, a small percentage of the beads turned out to be modern, but most of the beads were drilled through with diamond-tipped drill bits, a technique which was brought to our region in the Middle Ages. The real surprise was small group of beads which were perforated in a style that matched the 3rd millennium BCE – one, pecked with a stone chisel, may be as old as the Early Bronze age, and 3 others, drilled with a copper bit, seem to originate in the Intermediate Bronze age.

The Intermediate Bronze age (2200–2000 BCE) is a bit of an enigmatic period in the history of the Land of Israel. At the end of the Early Bronze age, urban communities shrunk or disappeared completely, and most of our knowledge of the following period comes from artifacts found in burial caves. Dr. Ludvik wrote his doctoral thesis on the beads from this period, from throughout the country, Jordan, and Sinai, including a group of beads found in a cave, on the Mount of Olives, right outside Jerusalem. So, with his familiarity of the drilling technique, as well as the shape and materials of the beads, he was able to securely date them to this ancient era.

What does this teach us? Frankly, it’s still too early to tell. Beads, as all jewelry, tend to have a very long usage period, and can be passed on for many generations. There have even been documented necklaces which incorporated beads centuries older than others. So, as responsible archaeologists, finding these beads doesn’t cause us to immediately rush and announce the existence of a jewelry workshop from five thousand years ago, but for a time period of which we know so little about, every extra bit is exciting!

You can read the full article in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences to learn more about Dr. Ludvik’s methodology and the other beads studied from our collection.

Discover more from The Temple Mount Sifting Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Nowadays some drill a hole then round off the beads.